The Gut

This article gives a brief overview of the gut and how the gut

works.

What is the gut?

The gut

(gastrointestinal tract) is the long tube that starts at the mouth and ends at

the anus.

Where is the gut found?

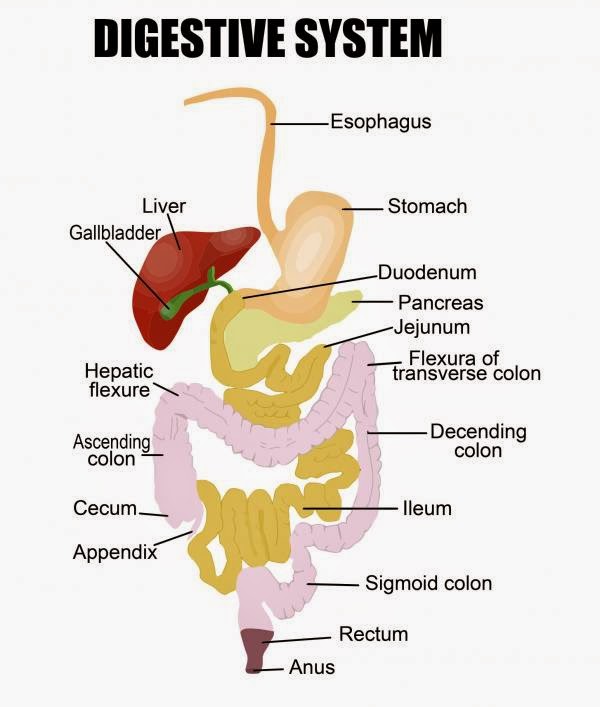

The mouth is the first part of the gastrointestinal tract. When

we eat, food passes down the oesophagus (gullet), into the stomach, and then

into the small intestine. The small intestine has three sections - the

duodenum, jejunum and ileum. The duodenum is the first part of the small

intestine and follows on from the stomach. The duodenum curls around the

pancreas creating a c-shaped tube. The jejunum and ileum make up the rest of

the small intestine and are found coiled in the centre of the abdomen. The

small intestine is where food is digested and absorbed into the bloodstream.

Following on from the ileum is the first part of the large intestine, called the caecum. Attached to the caecum is the appendix. The large intestine continues upwards from here and is known as the ascending colon. The next part of the gut is called the transverse colon because it crosses the body. It then becomes the descending colon as it heads downwards. The sigmoid colon is the S shaped final part of the colon which leads on to the rectum. Faeces is stored in the rectum and pushed out through the anus when you go to the toilet. The anus is a muscular opening that is usually closed unless you are passing stool.

The large intestine absorbs water, and contains food that has not been digested, such as fibre.

Following on from the ileum is the first part of the large intestine, called the caecum. Attached to the caecum is the appendix. The large intestine continues upwards from here and is known as the ascending colon. The next part of the gut is called the transverse colon because it crosses the body. It then becomes the descending colon as it heads downwards. The sigmoid colon is the S shaped final part of the colon which leads on to the rectum. Faeces is stored in the rectum and pushed out through the anus when you go to the toilet. The anus is a muscular opening that is usually closed unless you are passing stool.

The large intestine absorbs water, and contains food that has not been digested, such as fibre.

What does the gut do?

The gut processes food - from the time it is first eaten until

it is either absorbed by the body or passed out as faeces. The process of

digestion begins in the mouth. Here your teeth and enzymes (chemicals made by

the body) begin to break down food. Muscular contractions help to move food

into the oesophagus and on to the stomach. Chemicals produced by cells in the

stomach begin the major work of digestion.

While some foods and liquids are absorbed through the lining of the stomach, the majority are absorbed in the small intestine. Muscles in the wall of the gut mix your food with the enzymes produced by the body. They also move food along towards the end of the gut.

Food that can't be digested, waste substances, bacteria and undigested food all get passed out as faeces.

While some foods and liquids are absorbed through the lining of the stomach, the majority are absorbed in the small intestine. Muscles in the wall of the gut mix your food with the enzymes produced by the body. They also move food along towards the end of the gut.

Food that can't be digested, waste substances, bacteria and undigested food all get passed out as faeces.

How does it work?

The mouth contains salivary glands which release saliva. When

food enters your mouth the amount of saliva increases. Saliva helps to

lubricate food and contains enzymes that start chemically digesting your meal.

Teeth break down large chunks into smaller bites. This gives a greater surface

area for the body's chemicals to work on. Saliva also contains special

chemicals that help stop bacteria from causing infections.

The amount of saliva released is controlled by your nervous system. A certain amount of saliva is normally continuously released. The sight, smell or thought of food can also stimulate your salivary glands.

To pass food from your mouth to the oesophagus you must be able to swallow. Your tongue helps to push food to the back of the mouth. Then the passages to your lungs close and you stop breathing for a short time. The food passes into your oesophagus. The oesophagus releases mucous to lubricate food. Muscles push your meal downwards towards the stomach.

The stomach is a j-shaped organ found between the oesophagus and duodenum. When empty it is about the same size as a large sausage. Its main function is to help digest the food you eat. The other main function of the stomach is to store food until the gut is ready to receive it. You can eat a meal faster than your intestines can digest it.

Digestion involves breaking food down into its most basic parts. It can then be absorbed through the wall of the gut into the bloodstream and transported around the body. Just chewing food doesn't release the essential nutrients, so enzymes are needed.

The wall of the stomach has several different layers. The inner layers contain special glands. These glands release enzymes, hormones, acid and other substances. These secretions form gastric juice, the liquid found in the stomach.

Muscle and other tissue form the outer layers. A few minutes after food enters the stomach the muscles within the stomach wall start to contract (tighten). This creates gentle waves in the stomach contents. This helps to mix the food with gastric juice.

Using its muscles the stomach then pushes small amounts of food (now known as chyme) into the duodenum. The stomach has two sphincters, one at the bottom and one at the top. Sphincters are bands of muscles that form a ring. When they contract the opening the control closes. This stops chyme going into the duodenum before it is ready.

Digestion of food is controlled by your brain, nervous system and various hormones released in the gut. Even before you begin eating, signals from your brain travel via nerves to your stomach. This causes gastric juice to be released in preparation for food arriving. Once food reaches the stomach, receptors (special cells which detect changes in the body) send their own signals. These signals cause the release of more gastric juice and more muscular contractions.

When food starts to enter the duodenum this sets off different receptors. These receptors send signals that slow down the muscular movements and reduce the amount of gastric juice made by the stomach. This helps to stop the duodenum being overloaded with chyme.

The duodenum, jejunum and ileum make up the small intestine. The first part of the duodenum receives food from the stomach. It also receives bile from the gallbladder via the bile duct, and pancreatic enzymes made by cells in the pancreas via the pancreatic duct. Pancreatic enzymes are needed to break down and digest food. Bile, although not essential, helps in the digestion of fatty foods. Cells and glands in the lining of the the small intestines also produce intestinal juice that helps digestion. Contractions in the wall of the small intestine help to mix food and to move it along.

The small intestine also has special features which help to increase the amount of nutrients absorbed by the body. The inner layer of the small intestine has millions of what are known as villi. These are tiny finger like structures with small blood vessels inside. They are covered by a thin layer of cells. Because this layer is thin it allows the nutrients released by digestion to enter the blood. Most of the important nutrients needed by the body are absorbed at different points of the small intestine.

Following on from the ileum is the large intestine. The inside of the large intestine is wider than the small intestine. It does not contain villi, and mainly absorbs water. Bacteria in the large intestine also help with the final stages of digestion. Once chyme has been in the large intestine for 3-10 hours it becomes semi solid. This is because most of the water has been removed. These remnants are now known as faeces.

Movements of the muscles found in the large intestine help to digest the chyme and move faeces towards the rectum. When faeces are present in the rectum the walls of the rectum stretch. This stretch activates special receptors. These receptors send signals via nerves to the spinal cord. The spinal cord signals back to the muscles in the rectum, increasing pressure on the first sphincter of the anus. The second, or external sphincter of the anus is under voluntary control. This means you can decide whether you will open your bowels or not. Young children have to learn to control this during toilet training.

The amount of saliva released is controlled by your nervous system. A certain amount of saliva is normally continuously released. The sight, smell or thought of food can also stimulate your salivary glands.

To pass food from your mouth to the oesophagus you must be able to swallow. Your tongue helps to push food to the back of the mouth. Then the passages to your lungs close and you stop breathing for a short time. The food passes into your oesophagus. The oesophagus releases mucous to lubricate food. Muscles push your meal downwards towards the stomach.

The stomach is a j-shaped organ found between the oesophagus and duodenum. When empty it is about the same size as a large sausage. Its main function is to help digest the food you eat. The other main function of the stomach is to store food until the gut is ready to receive it. You can eat a meal faster than your intestines can digest it.

Digestion involves breaking food down into its most basic parts. It can then be absorbed through the wall of the gut into the bloodstream and transported around the body. Just chewing food doesn't release the essential nutrients, so enzymes are needed.

The wall of the stomach has several different layers. The inner layers contain special glands. These glands release enzymes, hormones, acid and other substances. These secretions form gastric juice, the liquid found in the stomach.

Muscle and other tissue form the outer layers. A few minutes after food enters the stomach the muscles within the stomach wall start to contract (tighten). This creates gentle waves in the stomach contents. This helps to mix the food with gastric juice.

Using its muscles the stomach then pushes small amounts of food (now known as chyme) into the duodenum. The stomach has two sphincters, one at the bottom and one at the top. Sphincters are bands of muscles that form a ring. When they contract the opening the control closes. This stops chyme going into the duodenum before it is ready.

Digestion of food is controlled by your brain, nervous system and various hormones released in the gut. Even before you begin eating, signals from your brain travel via nerves to your stomach. This causes gastric juice to be released in preparation for food arriving. Once food reaches the stomach, receptors (special cells which detect changes in the body) send their own signals. These signals cause the release of more gastric juice and more muscular contractions.

When food starts to enter the duodenum this sets off different receptors. These receptors send signals that slow down the muscular movements and reduce the amount of gastric juice made by the stomach. This helps to stop the duodenum being overloaded with chyme.

The duodenum, jejunum and ileum make up the small intestine. The first part of the duodenum receives food from the stomach. It also receives bile from the gallbladder via the bile duct, and pancreatic enzymes made by cells in the pancreas via the pancreatic duct. Pancreatic enzymes are needed to break down and digest food. Bile, although not essential, helps in the digestion of fatty foods. Cells and glands in the lining of the the small intestines also produce intestinal juice that helps digestion. Contractions in the wall of the small intestine help to mix food and to move it along.

The small intestine also has special features which help to increase the amount of nutrients absorbed by the body. The inner layer of the small intestine has millions of what are known as villi. These are tiny finger like structures with small blood vessels inside. They are covered by a thin layer of cells. Because this layer is thin it allows the nutrients released by digestion to enter the blood. Most of the important nutrients needed by the body are absorbed at different points of the small intestine.

Following on from the ileum is the large intestine. The inside of the large intestine is wider than the small intestine. It does not contain villi, and mainly absorbs water. Bacteria in the large intestine also help with the final stages of digestion. Once chyme has been in the large intestine for 3-10 hours it becomes semi solid. This is because most of the water has been removed. These remnants are now known as faeces.

Movements of the muscles found in the large intestine help to digest the chyme and move faeces towards the rectum. When faeces are present in the rectum the walls of the rectum stretch. This stretch activates special receptors. These receptors send signals via nerves to the spinal cord. The spinal cord signals back to the muscles in the rectum, increasing pressure on the first sphincter of the anus. The second, or external sphincter of the anus is under voluntary control. This means you can decide whether you will open your bowels or not. Young children have to learn to control this during toilet training.

Some disorders of the gut

- Acid Reflux &

Oesophagitis

- Anal Fissure

- Appendicitis

- Barrett's Oesophagus

- Cancer of the Bowel

- Cancer of the Liver

- Cancer of the

Oesophagus

- Cancer of the

Pancreas

- Cancer of the Stomach

- Cholecystitis

- Coeliac Disease

- Constipation

- Crohn's Disease

- Cystic Fibrosis

- Diarrhoea

- Diverticula

- Duodenal Ulcer

- Dyspepsia

- Gallstones

- Gastroenteritis

- Haemorrhoids (Piles)

- Helicobacter Pylori

& Stomach Pain

- Hernia

- Hiatus Hernia

- Irritable Bowel

Syndrome

- Mesenteric Adenitis

- Pancreatitis

- Pruritus Ani (Itchy

Bottom)

- Pyloric Stenosis

- Rectal Bleeding

(Blood in Faeces)

- Stomach (Gastric)

Ulcer

- Threadworms

- Toddler's Diarrhoea

- Ulcerative Colitis

For more details & Consultation Feel free to contact us.

Vivekanantha Clinic Consultation Champers at

Chennai:- 9786901830

Panruti:- 9443054168

Pondicherry:- 9865212055 (Camp)

For appointment please Call us or Mail Us

For appointment: SMS your Name -Age – Mobile Number - Problem in Single word - date and day - Place of appointment (Eg: Rajini - 99xxxxxxx0 – Pigmentation Disorders – 21st Oct, Sunday - Chennai ), You will receive Appointment details through SMS

==---==